Tour historic buildings on original sites

Strawbery Banke Museum is unique amongst outdoor history museums in preserving a complete neighborhood’s evolution of over 350 years, with most of the historic houses on their original sites.

Tour historic buildings ranging from elegant mansions and working-class homes in a waterfront neighborhood to a colonial tavern that welcomed both Patriots and Loyalists, a 1940s corner store, and a cooper’s shop.

-

Abbott House & Store

Year built: 1720

Year of interpretation: 1943

The home and store of Walter and Bertha Abbott stands on Jefferson Street. They opened their store in 1919, and after Walter died in 1938, Bertha operated the store until 1950. Mom-and-pop stores like theirs were threatened with extinction by the development of supermarkets but received a new lease on life in World War II when there was a local population explosion and war-time rationing. -

Chase House

Year built: 1762

Year of interpretation: 1818

The Chase House, on the corner of Court and Washington Street, is one of the grandest Georgian structures at Strawbery Banke. The Chase Family, Portsmouth merchants, lived in the house for over a century. Stephen Chase was a graduate of Harvard College, and his wife Mary was related to the famous Pepperrells of Kittery, merchants involved in the West India trade. When Stephen Chase died in 1805, his widow and two sons, William and Theodore, continued to live in the house. The last Chase to live here was William’s widow, Sarah Blunt Chase, who died in 1881. At that time, Theodore’s son bought the house and donated it as a home for orphaned children. When the needs of the Chase Home for Children outgrew the house in the early twentieth century, it was purchased as a residence by Mrs. Thomas Bailey Aldrich, who had opened her husband’s boyhood home, two doors down the street, as a memorial to him only a few years before. -

Cotton Tenant House North

Year built: circa 1835

Horticulture Learning Center

Temporarily closed to visitors for reinterpretationLeonard Cotton bought this property in 1834 and shortly thereafter had the Cotton Tenant Houses erected, which are the last of the extant houses to be constructed in the Strawbery Banke neighborhood. By the 1830s, Cotton was a successful retail grocer on Pleasant Street. His businesses were successful, for he began purchasing investment properties such as this one on Atkinson Street.

Today, Cotton Tenant House North houses the Horticulture Learning Center where visitors experience programs inspired by the Museum’s heirloom gardens, plants, and investigations based on garden-related items in the historical collections. -

Cotton Tenant House South

Year built: circa 1835

Weaving exhibition

Leonard Cotton bought this property in 1834 and shortly thereafter had the Cotton Tenant Houses erected, which are the last of the extant houses to be constructed in the Strawbery Banke neighborhood. By the 1830s, Cotton was a successful retail grocer on Pleasant Street. His businesses were successful, for he began purchasing investment properties such as this one on Atkinson Street.Today, Cotton Tenant House South houses the hands-on weaving exhibit with several looms available for visitors to try under the direction of an interpreter. This space is staffed based on the availability of our skilled craftspeople.

-

Pridham House

Year built: 1795

Year of interpretation: 1950sThe Shapley-Drisco-Pridham House shows the domestic settings of two very different generations of occupancy. The right half shows how the Shapley family lived here in the 1790s and the left half interprets how the last families lived here in the 1950s, before Urban Renewal and the subsequent founding of Strawbery Banke.

The Pridham family lived on the left side of the building after it was changed into a duplex. In the decades prior, the neighborhood experienced socio-economic decline and as a result, many dwellings in Puddle Dock were converted to multi-family homes. The house is restored to depict the life of the young Pridham family. Blanche Pridham worked at the Liberty Street Laundry, Joe Pridham worked at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard after returning from WWII, and their young son Sherman attended the nearby Haven School. The neighborhood was tight-knit; picnics and outings were popular, as was the Puddle Dockers baseball team and playing in the scrap metal yards. Most neighbors worked at jobs in the Navy Yard.

-

Dinsmore Shop

Year built: circa 1800

Year moved to Strawbery Banke: 1970

Cooper Demonstration

The Dinsmore shop has housed a variety of traditional crafts, primarily blacksmiths and most recently a cooper. Both of these trades were crucial parts of urban and maritime life. Portsmouth’s coopers produced vast quantities of barrel staves for export, particularly to the West Indies where they were finished and shipped out filled with sugar, molasses, rum, and other local products. Today, Ron Raiselis, Resident Master Cooper, performs coopering demonstrations for visitors several days a week during the season. This space is staffed based on the availability of our skilled craftspeople. -

Goodwin Mansion

Year built: 1811

Year of interpretation: 1870

Year moved to Strawbery Banke: 1963The Goodwin Mansion served as the home of Ichabod Goodwin and his wife, Sarah Parker Rice Goodwin. Ichabod started his career working in a counting house as a teenager and later became a supercargo, overseeing a ship's cargo and ensuring its sale. He worked hard and soon became the captain of his ship. However, with the advent of the railroad, Ichabod decided to give up his life at sea and focus on merchant activities. This included acquiring Southern cotton, picked by enslaved Africans, for Northern mills. He served as the President of the Portsmouth Steam Factory, which was one of these mills.

Ichabod and Sarah married in 1827 and purchased the mansion in 1832, where they went on to raise their seven children. Sarah spent her days looking after their children, writing, and planning the elaborate garden, which Strawbery Banke recreated where the mansion stands today. Goodwin was elected Governor of New Hampshire in 1859 and 1860.

The Goodwin Mansion is one of the few buildings that were moved to Puddle Dock. It was built in the Federal style and still retains much of its original Federal woodwork. However, several Greek Revival changes have been made over the years, including the addition of coal-burning grates and marble mantelpieces. A significant modification was made to the building after 1850 when gas was first introduced in Portsmouth. This can be seen in the formal parlor, where there is an existing gas pipe surrounded by a plaster rosette.

-

Jackson House

Year built: 1790

Year of interpretation: 1790 to the presentThe Joshua Jackson House was built around 1790 by the Jackson family. However, it was sold to a new owner soon after. Today, this side-gabled house serves as an example of preservation as defined by the National Parks Service. Instead of being restored to a particular period, it showcases changes over time. The house features Federal Period woodwork and mantel pieces, as well as Twentieth-century wallpaper covering the horsehair lathe. Alterations have been preserved so visitors can understand how the house has been changed architecturally, decoratively, and technologically over time.

Visitors can also learn about the life of residents of Puddle Dock in the Twentieth Century through informational panels. Strawbery Banke plans to include audio recordings of oral histories from some of these residents in the future.

-

Jones House

Year built: circa 1790

People of the Dawnland exhibitionJoshua Jones purchased this house in 1796, becoming its longest resident as he lived there until he died in 1843. Architecturally, the house is an interesting look at how Georgian, or Colonial, architecture gave way to the Federal Style.

Today, Jones House hosts an interactive exhibit exploring Abenaki culture, arts, foodways, and storytelling traditions. Visitors will learn more about the Abenaki and Wabanaki peoples of Northern New England, Southern Quebec, and the Canadian Maritime Provinces; both past and present. The "People of the Dawnland" exhibit invites visitors to touch traditional basket weaves, play with a cornhusk doll, and see what plants are growing in the Abenaki teaching garden. Archaeologists at Strawbery Banke have uncovered pieces of pottery, stone tools, and tent holes that demonstrate the presence of the Abenaki. For over 12,000 years, they have visited the Seacoast seasonally for hunting, fishing, and food preparation. This exhibit describes the locations of Tribal groups from present-day Newfoundland to the mid-Atlantic, their shared traditions, beliefs, and resources of their trade networks, and the family relationships of the Abenaki and other Indigenous peoples who are still here in New Hampshire.

-

Lowd House

Year built: circa 1810

Woodworking Tools of the Nineteenth Century exhibitionPeter Lowd, Cooper (barrel maker), purchased this house from neighbor James Drisco in 1824. The house is a simple vernacular Federal building but features elegant examples of woodwork, including the front door surround with its delicate fanlight and pilasters, and some existing interior trim. The southern portion of the house was added to an early Georgian structure, resulting in the structure's L-shape.

Lowd's work as an artisan makes the house appropriate for an exhibition on trades. In the Lowd House, visitors view woodworking tools of the nineteenth century. Wood was an important resource for Portsmouth from the City's founding through the advent of the Industrial Revolution. The Lowd House exhibit features trades such as boat building, brewery work, cabinet making, block making, tools, and coopering.

-

Penhallow-Cousins House

Temporarily closed to visitors for restoration

Year built: circa 1750

Period of interpretation: 1937-1943

Year moved to Strawbery Banke: 1862

The Penhallow-Cousins House was originally built in 1750 as a single-family home. It was moved to its present location in 1862 from where it was built nearby. At that time, the house was altered into a multi-family home, and by 1937, the Cousins family was residing in one-third of the building at 91 Washington Street.Kenneth, Eleanor, and Geraldine (Jeri) Cousins lived in the house from 1937 to 1943. Oral histories from family and friends, archaeological evidence, and donated objects from family members have allowed the Museum to recreate the family home accurately. Jeri shared memories from her childhood in the 1930s and early 1940s, including the layout of her house, her experience as a Black child in a predominantly white community, and the lives of her parents. She has vivid stories of fishing with her grandfather, being watched by her neighbor “Aunt Kate,” where her family shopped, and what her mother cooked for Sunday dinner. Her parents worked in the service industry for wealthy families in Rye, Eleanor as a maid and Kenneth as a chauffeur. The Cousins’ story is one of the Great Migration and how a Black family made their way in Portsmouth.

The Penhallow-Cousins House is one of the last Strawbery Banke buildings to be restored and is expected to open in 2025.

-

Reproduction Wigwam

Temporarily Absent, Pending Reconstruction

Year built: 2021

Wigwam is the word for “house” in the Abenaki language. In 2021, museum staff worked with the Cowasuck Band of the Pennacook-Abenaki People and the Indigenous New Hampshire Collaborative Collective to build the frame for a wigwam on the museum grounds, near the location of a possible post mold uncovered during archaeological excavations in 2015.The frame of this Wigwam is made from young red maple saplings; however, red willow or swamp maple can be used. Saplings are bent and woven together to make a domed shape. Once the frame is constructed, it is tied together in order to ensure a secure structure. A doorway is created facing east, in the direction of the rising sun. A wigwam would typically then be covered with birch bark, red oak bark, or elm bark, in order to create a dry, warm shelter that would last anywhere from 2 to 5 years. However, the structure at Strawbery Banke has been left uncovered for now so that visitors can see the internal structure.

-

Rider-Wood House

Year built: 1800

Period of interpretation: 1830sThe four-room dwelling of Rider-Wood is typical of the vernacular architecture of Puddle Dock and the surrounding South End. John and Mary Rider, immigrants from Devon, England, purchased the house in 1809 and added the shop ell by 1830. After John's death, Mary continued to operate the shop. The income allowed her to sponsor many of her nieces and nephews' voyages to America from England, and many lived with her until they settled.

Rider-Wood is an excellent example of how Strawbery Banke used archaeology to inform the interpretation of the house. Uncovered artifacts included ceramics, glass, animal bones, and more. Museum curators used this information to locate ceramics that matched ceramic sherds and enabled them to understand the family's diet.

-

Shapiro House

Year built: 1795

Year of interpretation: 1919

The Shapiro house was home to Sarah and Abraham Shapiro, and their daughter Mollie. Sarah and Abraham were Jewish immigrants from Anapol in the Ukraine. At this time, Puddle Dock was a crowded place. Many houses, which were once single-family homes, were converted into apartments where people from all different countries lived side by side. Downtown, horses and buggies were still traveling the streets, but automobiles were starting to become a more common sight. -

Shapley House

Year built: 1790

Period of interpretation: 1795Catherine and John Shapley built this house on the banks of the tidal inlet of Puddle Dock. John was a mariner and sailed his small ship from the dock that extended from the shore outside the house to fish and participate in the coastal trade. Small ships and gundalows tied up at the Shapley pier to unload goods the family sold in their first-floor shop. The couple's three daughters likely helped to tend to the shop.

Built as a single-family home, the two-story building demonstrates a plain vernacular style as building trends moved toward Federal period architecture. In the late nineteenth century, the building was split into a duplex, including removing a single front door and the addition of the separate two-door entrances visible today.

-

Sherburne House

Undergoing restoration. Open for tours during “Behind-The-Scenes Tours.”

Year built: 1695

The Sherburne House is one of the last three wood-framed houses of the 1600s in New Hampshire. This house is one of the main reasons that Strawbery Banke exists. In 1957, when faced with the imminent demolition of the house to clear a path for an Urban Renewal project, local advocates made the fate of the Sherburne House the focal point of a public effort to save the historic buildings of Portsmouth’s earliest neighborhood around Puddle Dock.John Sherburne, “mariner of New Castle,” purchased the land for the house in February of 1695 and added an adjacent plot eighteen months later. On that land, John Sherburne built a two-story, single-cell, and chimey-bay house with a gable roof and a façade gable sometime between 1695 and 1698, when he died.

-

Stoodley's Tavern

Year built: 1761

Year moved to Strawbery Banke: 1966

Education Center and Administrative Offices

James Stoodley kept The King’s Arms Tavern (built in 1753), on State Street. During the 1750s James Stoodley served in the French and Indian Wars as a British Ranger with Major Rogers. This tavern burned to the ground in 1761 and Stoodley immediately built the new one which survives today. The tavern was home to James Stoodley and his wife, a daughter Elizabeth, a son William, and two enslaved Africans, Frank, and Flora. Stoodley also hosted auctions in this building, enslaved Africans were sold in 1762 and 1767, along with barrels of rum and bags of cotton.

In 1964, Stoodley's Tavern was scheduled for demolition to make room for a new federal office building and post office. In 1966, the building was moved to Strawbery Banke and placed along Hancock Street. Today, the building serves as an Educational Center and offices and is used for year-round camp and classroom programs. -

Thomas Bailey Aldrich Memorial

Year built: circa 1797

Year of interpretation: 1909

Portsmouth merchant Thomas Bailey purchased this house in the first quarter of the nineteenth century. His grandson Thomas Bailey Aldrich visited his grandfather's home as a child and the location where he set his fictitious novel "A Story of a Bad Boy.". Although born in Portsmouth, Aldrich spent much of his youth in the South and New York City. As a young author, he found his first publication success in 1855 and joined literary circles that would see him form friendships with actor Edwin Booth, William Dean Howells, Mark Twain, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. He succeeded Howells as editor of the Atlantic Monthly, today known as The Atlantic.Upon his death, his widow Lilian purchased the Aldrich House and created a memorial to her husband. Each room was faithfully recreated using imagery from The Story of a Bad Boy. Thomas Bailey Aldrich House Museum opened in 1908, and Strawbery Banke restored Mrs. Aldrich's vision, which re-opened the house in the 1990s.

-

Walsh House

Year built: circa 1796

Year of interpretation: circa 1800

Located on Washington Street, adjacent to the Lawrence J. Yerdon Visitors Center, the Walsh House was built in c. 1796. It was named for sea captain Keyran Walsh, who owned the property from 1797-1807. Walsh, who lived in Portsmouth from 1782 on, captained ships and successfully traded in New Hampshire lumber and West India goods, traveling to ports around the Atlantic. While successful in his trade, Walsh was in a dangerous occupation, battling restrictive Spanish trade laws and trying to avoid the British Navy. In 1799, he lost his ship and her cargo after an encounter with a British man-of-war, and he died on a voyage from South America to Charleston, South Carolina, in 1807. In 1969, the house was moved about 80 feet north of its original location and was placed on a new foundation.The hands-on exhibit of the Captain Walsh House creates a fully immersive experience that brings the world of a sea captain and his family to life circa 1800. Unlike the Museum’s other furnished and exhibit houses, the Walsh House’s first-floor rooms are furnished with touchable, reproduction objects interpreting the home and life of a sea captain and his family circa 1800. Visitors are invited to sit at the dining table, lie on the bed, open drawers, and try on costumes to better understand everyday life in 1802 and draw connections between the past and present.

-

Wheelwright House

Year built: 1784

Historic Foodways DemonstrationWheelwright House is a simple Georgian structure with notable woodwork, including a triangular door pediment, mimicked over the first floor and side windows, and the fluted pilasters flanking the front door. John Wheelwright captained merchant vessels out of Portsmouth Harbor and when the American Revolution began, he served aboard the Portsmouth-built Raleigh and various privateering ships. When he died in debt to his creditors, his wife Elizabeth stayed in one-third of the house after it was sold at auction, as provisioned by inheritance laws at the time.

Visitors to Wheelwright today will be greeted by a demonstration of how food was prepared in the eighteenth century. Interpreters show guests how they gather and store seasonal ingredients, from the museum gardens, to aid in cooking over an open hearth. For example, hearth cooks may prepare an apple pie but also show how apples are dried or made into chutney for use over the winter months.

-

William Pitt Tavern

Year Built: 1766

Year of Interpretation: 1777

Pitt Tavern was the home of John Stavers, an English immigrant, and his family who settled in Portsmouth around 1750. Built in 1766, the tavern was not just the Stavers’ family home, but their place of business. Pitt Tavern served another important function in the community by being the Portsmouth terminus of the Flying Stage-Coach, which traveled between Portsmouth and Boston. Mr. Stavers also owned enslaved people, who provided much of the labor that kept the tavern and stagecoach line running. -

Yeaton-Welch House

Temporarily closed to visitors for restoration

Year built: between 1794-1803

Situated at the very center of the Museum site, facing Puddle Dock, the Yeaton-Welch House is one of the three remaining houses on the site in need of full restoration. For many years, the house has served as a storage area for the Museum’s archeological materials.Plans are underway to restore the interior of the house and interpret the Welch family, Irish immigrants who were long-term residents of the Yeaton-Welch House from circa 1855 to 1910.

Authentic recreations of rooms from the 1860s and early 1900s will highlight both struggle and resilience, while artifacts uncovered on-site will connect the Welches’ journey to Portsmouth’s broader immigrant past. Exhibits will also explore anti-Irish sentiment of the times, social and sanitary reforms, and the impact of the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, where Michael Welch found steady work.

-

Timothy Winn House

Year built: 1795

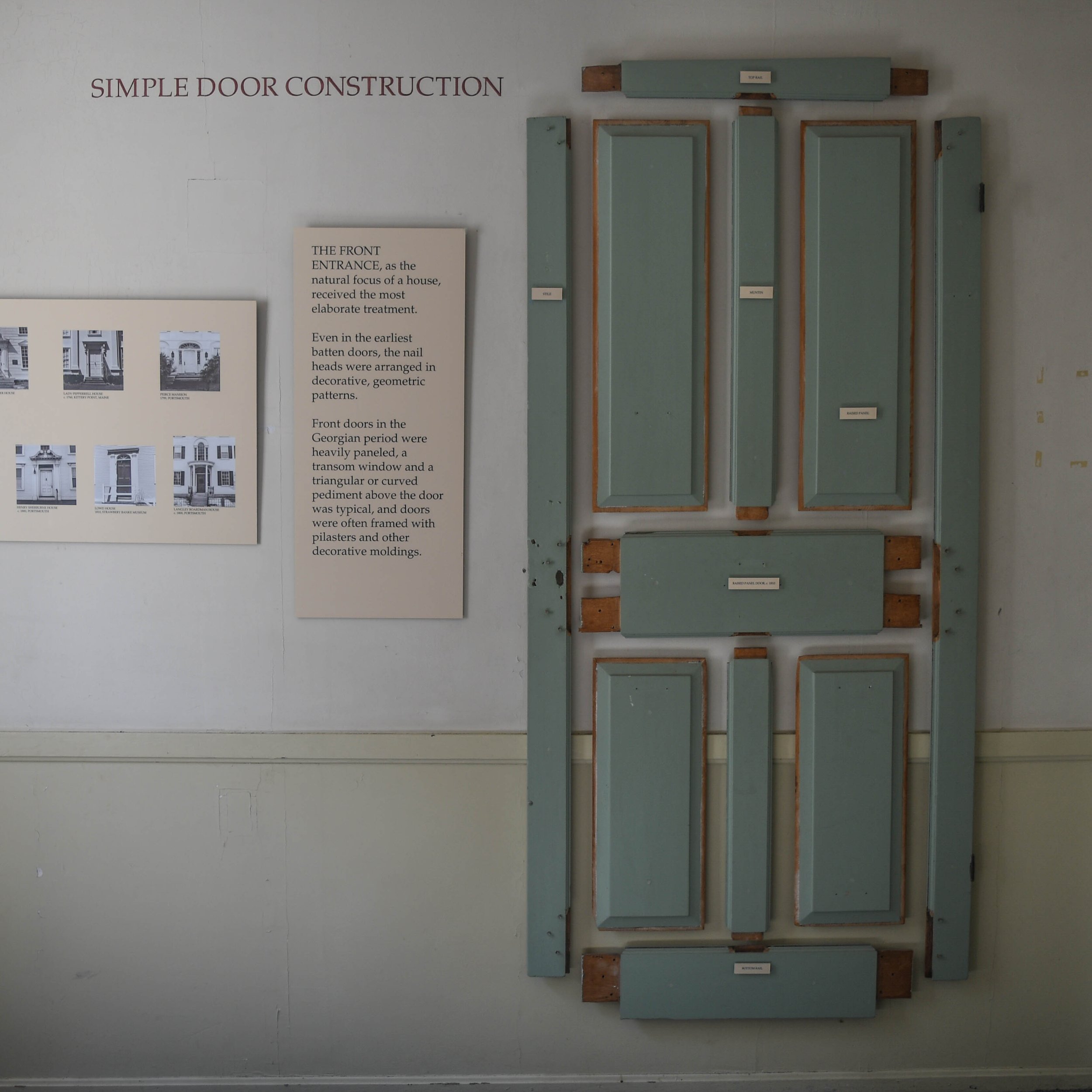

To Build a House exhibitionTimothy Winn built this house right next to his brother-in-law's newly built house. Though they look like they share a common wall, the Winn and Yeaton Houses each have their own separate frame. The interiors of the two homes are distinctly different. Winn House was built with a central hallway design and two chimneys on each side. The two rear stairways and two kitchens reflect that this house was designed for two-family occupancy. In the twentieth century, the large Winn House was divided further into apartments.

Winn House contains an exhibit entitled "To Build A House." This exhibit, partially funded by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, shows the various steps in constructing a house of this period, and displays tools of the craftsmen who built such houses.

-

Yeaton House

Year built: circa 1795

Port of Portsmouth: War, Trade & Travel ExhibitionYeaton House, with a central chimney and stair hall, demonstrates the architectural transition from the Georgian to the Federal style with interior paneled walls, denticulated crown moulding, and stylized fireplace surrounds.

The Port of Portsmouth exhibition explores the maritime history of Portsmouth and how it affected the lives of Puddle Dockers. A largely working-class neighborhood, Puddle Dock supplied the workforce to build large ships, harvest the rich waters of the Piscataqua, crew trade missions and war-going vessels, and offer foreign goods for sale. First-person accounts from aboard the USS Kearsarge provide insight into the Civil War, and eighteenth-century letters reveal that the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard was where the Continental Navy was launched. The exhibit features numerous models of ships built in Portsmouth, a recreated shipping office, and decorative arts relating to the maritime industry. A small room is dedicated to the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard.